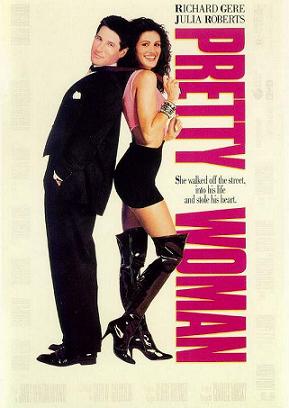

Now celebrating its 25th anniversary, Pretty Woman remains an all-too-familiar ode to wealth and power . . . with a gender twist.

Pretty Woman is Julia Roberts' film, for better or worse. Twenty-five years after it was released, the movie is at once beloved and loathed, and that holds for Roberts' role in it as well. When people praise Pretty Woman, they praise Julia Roberts; when they despise the film, they tend to despise her and/or her character, Vivian, the "hooker" with a heart of gold. Darryl Hannah, who turned down the role of Vivian, notably kicked the film and the character in 2007:

"They sold it as a romantic fairytale when in fact it's a story about a prostitute who becomes a lady by being kept by a rich and powerful man. I think that film is degrading for the whole of womankind."

It's easy to see why Vivian is the focus of attention; love the movie or hate it, Roberts is a magnetic actor, infusing an indifferently written character with vulnerability, joy, and glamor—and occasionally even with a knowingness that the film itself does its best to avoid. Richard Gere as Edward, on the other hand, is mostly just voting "present." The leading man is a repressed squib, whose facial expression shifts between vaguely interested and vaguely constipated. What emotions he has are displayed through modulated ejaculations of cash.

And yet, narratively, Pretty Woman is about Edward, not Vivian. The film starts with him at a party, breaking up with his girlfriend (who doesn't want to be at his beck and call) and, with a detour or two, the plot sticks with him throughout. He picks Vivian up, he decides to retain her for the week—but more than that, the business story, about taking over a ship-building company and selling it for parts, is all his. The movie takes place in his world, mostly among men in suits. It's his character transformation (from wounded asshole repressed businessman who breaks up companies to healthy asshole businessman who builds military hardware to kill people), which drives the narrative. At the end, the movie talks a bit about how Viv has changed, but that's mostly just words and a different wardrobe. The script is focused on Edward's soul, not hers.

As it happens, this isn't actually unusual in the romance genre, as explained in the 1992 essay collection Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women (released not long after Pretty Women itself). The essays are written by romance novelists, and many of them argue that in romance, the male characters are often the focus, not the women.

In particular, Laura Kinsale, in an essay titled "The Androgynous Reader," points out that: "It is a commonly accepted truism that when a woman reads a romance she is 'identifying' with the heroine." But, Kinsale says, that isn't necessarily so. In fact, she says, her readers, and romance novel readers in general, demand more focus on the hero than the heroine. That's why, these days, large numbers of romance novels include sections written from the hero's point of view. Kinsale says this shifts the reader's experience in a powerful way:

"What reading a romance becomes, then,is the experience of 'what a courtship feels like,' but a courtship carried out entirely between myself and myself. This heroine is holding my place (or perhaps I even like her enough to identify with her to an extent) and I am the hero. That is why romance readers are not, and never have been, intimidated by what [romance novelist Jayne Ann] Krentz calls the 'alpha male' hero, the 'retrograde, old-fashioned, macho, hard-edged man'—because the alpha male hero is themselves."

According to Kinsale, women viewers would not identify with Vivian—or not just with Vivian. They'd identify with Edward, the old-fashioned wielder of power. The dream is not to be Edward's doll, buoyed up by his power—the dream is to be Edward, and wield that power yourself. "People are looking at me," Vivian says nervously as she walks through a ritzy part of town. To which Edward responds, "They're not looking at you. They're looking at me."

If Edward is the thing to look at, if he's the point of identification, then the film isn't about relying on men, so much as it's about taking the place of men. The famous line at the end where Edward compares himself to a rescuing prince, and Vivian says that the princess will rescue him right back, doesn't just mean that Viv and Edward are equals. It means that they're the same person; their positions are interchangeable. Likewise, when Vivian tells Edward, "I think you have a lot of special gifts," she's echoing and mocking his own words to her when he was telling her she could find a better job. But she's also underlining the fact that the gift she has is to be him (and possibly vice versa). Edward/Vivian is a possibility of power, glamor, sexiness, and love. The fun is in being both, not in one being subordinate to the other.

None of that makes Pretty Woman a good movie. It's still crass and ugly and stupid in most respects—and its casual treatment of sex workers as objects of pity and lurid excitement is gross (as sex workers like Lolo de Sucre have pointed out). But its crass, ugly stupidity starts to look less like a particular example of women participating in their own degradation, and more like our society's standard crass, ugly, stupid worship of power and wealth. Edward as fantasy isn't so much different than James Bond or Batman as fantasy or, for that matter, Christian Grey as a fantasy. The dream is wealth, power, and control, all wrapped in a patina of goodness and justice. James Bond shoots the bad guy and wears elegant suits; Edward wears elegant suits and generously doesn't break up the company he acquired. One's a spy story, one's a romance, but it seems like they both fit in the broader American genre of shallow empowerment fiction.

That genre is wearisome and degrading, but I don't know that it's really fair to blame its failings on Julia Roberts, Vivian, or even Pretty Woman itself.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)